- Introduction

- Scripting Philosophy

- Script Organization

- Debugging and Auditing

- Common Scenarios

- User Input Best Practices

- Conditionally Require Manual User Input Steps

- Outputing Extra Information to a TestRunner Test Report

- Getting the Most Recent Value of a Telemetry Point from Multiple Packets

- Checking Every Single Sample of a Telemetry Point

- Using Variables in Mnemonics

- Using Custom wait_check_expression

- COSMOS Scripting Differences from Regular Ruby Scripting

- When Things Go Wrong

- Advanced Topics

- Further Reading

Scripting Best Practices

Introduction

This guide aims to provide the best practices for using the scripting capabilities provided by COSMOS. Scripts are used to automate a series of activities for operations or testing. The goal of this document is to ensure scripts are written that are simple, easy to understand, maintainable, and correct. Guidance on some of the key details of using COSMOS’s ScriptRunner and TestRunner tools is also provided.

Scripting Philosophy

A Super Basic Script Example

Most COSMOS scripts can be broken down into the simple pattern of sending a command to a system/subsystem and then verifying that the command worked as expected. This pattern is most commonly implemented with cmd() followed by wait_check(), like the following:

cmd("INST COLLECT with TYPE NORMAL, TEMP 10.0")

wait_check("INST HEALTH_STATUS TYPE == 'NORMAL'", 5)

or similarly with a counter that is sampled before the command:

count = tlm("INST HEALTH_STATUS COLLECTS")

cmd("INST COLLECT with TYPE NORMAL, TEMP 10.0")

wait_check("INST HEALTH_STATUS COLLECTS >= #{count + 1}", 5)

90% of the COSMOS scripts you write should be the simple patterns shown above except that you may need to check more than one item after each command to make sure the command worked as expected.

KISS (Keep It Simple Stupid)

Ruby is a very powerful language with many ways to accomplish the same thing. Given that, always choose the method that is easiest to understand for yourself and others. While it is possible to create complex one liners or obtuse regular expressions, you’ll thank yourself later by expanding complex one liners and breaking up and documenting regular expressions.

Keep things DRY (Don’t Repeat Yourself)

A widespread problem in scripts written for any command and control system is large blocks of code that are repeated multiple times. In extreme cases, this has led to 100,000+ line scripts that are impossible to maintain and review.

There are two common ways repetition presents itself: exact blocks of code to perform a common action such as powering on a subsystem, and blocks of code that only differ in the name of the mnemonic being checked or the values checked against. Both are solved by removing the repetition using functions (also referred to as ‘methods’ in Ruby).

For example, a script that powers on a subsystem and ensures correct telemetry would become:

def power_on_subsystem

# 100 lines of cmd(), wait_check(), etc

End

Ideally, the above function would be stored in another file where it could be used by other scripts. If it is truly only useful in the one script, then it could be at the top of the file. The updated script would then look like:

power_on_subsystem()

# 150 lines operating the subsystem (e.g.)

# cmd(...)

# wait_check(...)

#...

power_off_subystem()

# Unrelated activities

power_on_subsystem()

# etc.

Blocks of code where only the only variation is the mnemonics or values checked can be replaced by functions with arguments like this:

def test_minimum_temp(enable_cmd_name, enable_tlm, temp_tlm, expected_temp)

cmd("TARGET #{enable_cmd_name} with ENABLE TRUE")

wait_check("TARGET #{enable_tlm} == 'TRUE;", 5)

wait_check("TARGET #{temp_tlm} >= #{expected_temp}", 50)

end

Use Comments Appropriately

Use comments when what you are doing is unclear or there is a higher-level purpose to a set of lines. Try to avoid putting numbers or other details in a comment as they can become out of sync with the underlying code. Ruby comments start with a # pound symbol and can be anywhere on a line.

# This line sends an abort command - BAD COMMENT, UNNECCESSARY

cmd("INST ABORT")

# Rotate the gimbal to look at the calibration target - GOOD COMMENT

cmd("INST ROTATE with ANGLE 180.0") # Rotate 180 degrees - BAD COMMENT

ScriptRunner vs TestRunner

COSMOS provides two unique ways to run scripts (also known as procedures). ScriptRunner provides both a script execution environment and a script editor. The script editor includes code completion for both COSMOS methods and command/telemetry item names. It is also a great environment to develop and test scripts. ScriptRunner provides a framework for users that are familiar with a traditional scripting model with longer style procedures, and for users that want to be able to edit their scripts in place.

TestRunner provides a more formal, but also more powerful, environment for running scripts. The name TestRunner comes from incorporating several of the concepts from software unit testing frameworks and applying them to system level test and operations. TestRunner, by design, has users break their scripts down into test suites, test groups, and test cases. Test Suites are the highest-level concept and would typically cover a large test procedure such as a thermal vacuum test, or a large operations scenario such as performing on orbit checkout. Test Groups capture a related set of test cases such as all the test cases regarding a specific mechanism. A Test Group might be a collection of test cases all related to a subsystem, or a specific series of tests such as an RF checkout. Test Cases capture individual activities that can either pass or fail. TestRunner allows for running an entire test suite, one or more test groups, or one or more test cases easily. It also automatically produces test reports, can easily gather meta data such as operator name, and produce associated data packages.

The correct tool for the job is up to individual users, and many programs will use both tools to complete their goals. For example, while formal tests are typically organized and run out of TestRunner, ScriptRunner is still used to run quick one-off scripts specific to a single target. Additionally, ScriptRunner makes a great editor for writing TestRunner scripts. It is recommended that users try both tools before deciding which will be best for their program.

Looping vs Unrolled Loops

Loops are powerful constructs that allow you to perform the same operations multiple times without having to rewrite the same code over and over (See the DRY Concept). However, they can make restarting a COSMOS script at the point of a failure difficult or impossible. If there is a low probability of something failing, then loops are an excellent choice. If a script is running a loop over a list of telemetry points, it may be a better choice to “unroll” the loop by making the loop body into a function, and then calling that function directly for each iteration of a loop that would have occurred.

For example:

10.times do |temperature_number|

check_temperature(temperature_number + 1)

end

If the above script was stopped after temperature number 3, there would be no way to restart the loop at temperature number 4. A better solution for small loop counts is to unroll the loop.

check_temperature(1)

check_temperature(2)

check_temperature(3)

check_temperature(4)

check_temperature(5)

check_temperature(6)

check_temperature(7)

check_temperature(8)

check_temperature(9)

check_temperature(10)

In the unrolled version above, the COSMOS “Start script at selected line” feature can be used to resume the script at any point.

Script Organization

Organize Scripts into Test Case Functions

Put each test case into a distinct function. This is the natural way to use TestRunner, but also works well in ScriptRunner. Putting your test cases into functions makes organization easy and gives a great high-level overview of what the overall script does (assuming you name the functions well). There are no bonus points for vague, short function names. Make your function names long and clear.

def test_1_heater_zone_control

puts "Verifies requirements 304, 306, and 310"

# Test code here

end

Using Classes vs Unscoped Functions

Classes in object-oriented programing allow you to organize a set of related methods and some associated state. The most important aspect is that the methods work on some shared state. For example, if you have code that moves a gimbal around, and need to keep track of the number of moves, or steps, performed across methods, then that is a wonderful place to use a class. If you just need a helper method to do something that happens multiple times in a script without copy and pasting, it probably does not need to be in a class.

class Gimbal

attr_accessor :gimbal_steps

def move(steps_to_move)

# Move the gimbal

@gimbal_steps += steps_to_move

end

def home_gimbal

# Home the gimbal

@gimbal_steps += steps_moved

end

end

def perform_common_math(x, y)

# Do the math and return result

end

gimbal = Gimbal.new

gimbal.home

gimbal.move(100)

gimbal.move(200)

puts "Moved gimbal #{gimbal.steps}"

perform_common_math(gimbal.steps, other_value)

Organizing Your Scripts into Separate Files

As your scripts become large with many methods, it makes sense to break them up into multiple files. Here is a recommended organization for your projects scripts/procedures.

| Folder | Description |

| config/targets/TARGET_NAME/lib | Place script files containing reusable target specific methods here |

| config/targets/TARGET_NAME/procedures | Place simple procedures that are centered around one specific target here |

| lib | Place script files containing reusable methods that span multiple targets here |

| procedures | Place high-level procedures that span targets here |

In your main procedure you will usually bring in the other files with instrumentation using load_utility.

load_utility('my_other_script')

Instrumented vs Uninstrumented Lines (require vs load)

COSMOS scripts are normally “instrumented”. This means that each line has some extra code added behind the scenes that primarily highlights the current executing line and catches exceptions if things fail such as a wait_check. If your script needs to use code in other files, there are a few ways to bring in that code. Some techniques bring in instrumented code and others bring in uninstrumented code. There are reasons to use both.

load_utility (and the deprecated require_utility), bring in instrumented code from other files. When COSMOS runs the code in the other file, ScriptRunner/TestRunner will dive into the other file and show each line highlighted as it executes. This should be the default way to bring in other files, as it allows continuing if something fails, and provides better visibility to operators.

However, sometimes you don’t want to display code executing from other files. Externally developed ruby libraries generally do not like to be instrumented, and code that contains large loops or that just takes a long time to execute when highlighting lines, will be much faster if included in a method that does not instrument lines. Ruby provides two ways to bring in uninstrumented code. The first is the “load” keyword. Load will bring in the code from another file and will bring in any changes to the file if it is updated on the next call to load. “require” is like load but is optimized to only bring in the code from another file once. Therefore, if you use require and then change the file it requires, you must restart ScriptRunner/TestRunner to re-require the file and bring in the changes. In general, load is recommended over require for COSMOS scripting. One gotcha with load is that it requires the full filename including extension, while the require keyword does not.

Finally, COSMOS scripting has a special syntax for disabling instrumentation in the middle of an instrumented script, with the disable_instrumentation function. This allows you to disable instrumentation for large loops and other activities that are too slow when running instrumented.

disable_instrumentation do

# Make sure nothing in here will raise exceptions!

5000000.times do

temp += 1

end

end

When Running Uninstrumented Code

Make sure that the code will not raise any exceptions or have any check failures. If an exception is raised from uninstrumented code, then your entire script will stop.

Debugging and Auditing

Built-In Debugging Capabilities

Both ScriptRunner and TestRunner have built in debugging capabilities that can be useful in determining why your script is behaving in a certain way. Of primary importance is the ability to inspect and set script variables.

To use the debugging functionality, first select the “Toggle Debug” option from the Script Menu. This will add a small Debug: prompt to the bottom of the tool. Any code entered in this prompt will be executed when Enter is pressed. To inspect variables in a running script, pause the script and then use “puts” to print out the value of the variable in the debug prompt.

puts variable_name

Variables can also be set simply by using equals.

variable_name = 5

If necessary, you can also inject commands from the debug prompt using the normal commanding methods. These commands will be logged to the ScriptRunner message log, which may be advantageous over using a different COSMOS tool like CmdSender (where the command would only be logged in the CmdTlmServer message log).

cmd("INST COLLECT with TYPE NORMAL")

Note that the debug prompt keeps the command history and you can scroll through the history by using the up and down arrows.

Breakpoints

While in Debug mode (Script -> Toggle Debug), you can right-click at any point in a script in ScriptRunner and select “Add Breakpoint”. This places a breakpoint on the selected line and the script will automatically pause when it hits the breakpoint. Once stopped at the breakpoint, you can evaluate the state of the system using telemetry screens or the built-in debugging capabilities.

Using Disconnect Mode

Disconnect mode is a feature of ScriptRunner and TestRunner that allows testing scripts in an environment without real hardware in the loop. Disconnect mode is started by selecting Script -> Toggle Disconnect. Once selected, the user is prompted to select which targets to disconnect. By default, all targets are disconnected, which allows for testing scripts without any real hardware. Optionally, only a subset of targets can be selected which can be useful for trying out scripts in partially integrated environments.

While in disconnect mode, commands to the disconnected targets always succeed. Additionally, all checks of disconnected target telemetry are immediately successful. This allows for a quick run-through of procedures for logic errors and other script specific errors without having to worry about the behavior and proper functioning of hardware.

Auditing your Scripts

ScriptRunner includes several tools to help audit your scripts both before and after execution.

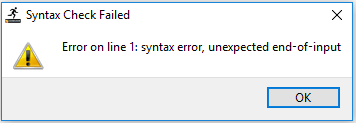

Ruby Syntax Check

The Ruby Syntax Check tool is found under the Script Menu. This tool uses the ruby executable with the -c flag to run a syntax check on your script. If any syntax errors are found the exact message presented by the Ruby interpreter is shown to the user. These can be cryptic, but the most common faults are not closing a quoted string, forgetting an “end” keyword, or using a block but forgetting the proceeding “do” keyword.

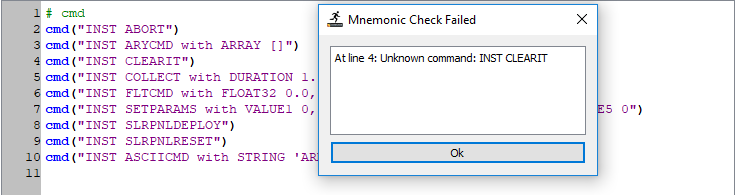

Mnemonic Check

The mnemonic check uses an algorithm to scan through your script for command and telemetry mnemonics and make sure they are known to COSMOS.

Generate Cmd/Tlm Audit

After you are done running your scripts, you can execute a Cmd/Tlm audit that will scan the ScriptRunner message log files and look for all cmd() lines and CHECK lines to know how many times each command was sent and how many times each telemetry point was checked. This audit reads one or more message log files and generates a CSV file with a count for each command and telemetry point.

Common Scenarios

User Input Best Practices

COSMOS provides several different methods to gather manual user input in scripts. When using user input methods that allow for arbitrary values (like ask() and ask_string()), it is very important to validate the value given in your script before moving on. When asking for text input, it is extra important to handle different casing possibilities and to ensure that invalid input will either re-prompt the user or take a safe path.

answer = ask_string("Do you want to continue (y/n)?")

if answer != 'y' and answer != 'Y'

raise "User entered: #{answer}"

end

temp = 0.0

while temp < 10.0 or temp > 50.0

temp = ask("Enter the desired temperature between 10.0 and 50.0")

end

When possible, always use one of the other user input methods that has a constrained list of choices for your users (message_box, vertical_message_box, combo_box).

Note that all these user input methods provide the user the option to “Cancel”. When cancel is clicked, the script is paused but remains at the user input line. When hitting “Go” to the continue, the user will be re-prompted to enter the value.

Conditionally Require Manual User Input Steps

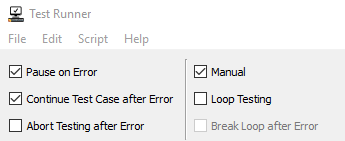

When possible, a useful design pattern is to write your scripts such that they can run without prompting for any user input. This allows the scripts to be more easily tested and provides a documented default value for any user input choices or values. To implement this pattern, all manual steps such as ask(), prompt(), and infinite wait() statements need to be wrapped with an if statement that checks the value of the $manual variable. If $manual is set, then the manual steps should be executed. If not, then a default value should be used.

# Set the $manual variable – Only needed in ScriptRunner

answer = ask("Prompt for manual entry (Y/n)?")

if answer == 'n' or answer == 'N'

$manual = false

else

$manual = true

end

if $manual

temp = ask("Please enter the temperature")

else

temp = 20.0

end

if !$manual

puts "Skipping infinite wait in auto mode"

else

wait

end

In TestRunner, there is a checkbox at the top of the tool called “Manual” that affects this $manual variable directly. In ScriptRunner you can also use the $manual pattern, but will need to build in an ask() at the top of your script to ask if the user wants to run manual steps, and then set the $manual variable appropriately.

Outputing Extra Information to a TestRunner Test Report

COSMOS TestRunner automatically generates a test report that shows the PASS/FAILED/SKIPPED state for each test case. You can also inject arbitrary text into this report with the current test case using Cosmos::Test.puts “Your Text”. Alternatively, you can simply use puts to place text into the ScriptRunner message log (in both TestRunner/ScriptRunner).

class MyTest < Cosmos::Test

def test_1

# The following text will be placed in the test report

Cosmos::Test.puts "Verifies requirements 304, 306, 310"

# Do the test here

# This puts line will show up in the sr_messages log file

puts "test_1 complete"

end

end

Getting the Most Recent Value of a Telemetry Point from Multiple Packets

Some systems include high rate data points with the same name in every packet. COSMOS supports getting the most recent value of a telemetry point that is in multiple packets using a special packet name of LATEST. Assume our target INST has two packets, PACKET1 and PACKET2. Both packets have a telemetry point called TEMP.

# Get the value of TEMP from the most recently received PACKET1

value = tlm("INST PACKET1 TEMP")

# Get the value of TEMP from the most recently received PACKET2

value = tlm("INST PACKET2 TEMP")

# Get the value of TEMP from the most recently received PACKET1 or PACKET2

value = tlm("INST LATEST TEMP")

Checking Every Single Sample of a Telemetry Point

When writing COSMOS scripts, checking the most recent value of a telemetry point normally gets the job done. The tlm(), tlm_raw(), etc methods all retrieve the most recent value of a telemetry point. Sometimes you need to perform analysis on every single sample of a telemetry point. This can be done using the COSMOS packet subscription system. The packet subscription system lets you choose one or more packets and receive them all from a queue. You can then pick out the specific telemetry points you care about from each packet.

id = subscribe_packet_data([["INST", "HEALTH_STATUS"]])

total = 0

100.times do

packet = get_packet(id)

value = packet.read("TEMP1")

total += value

end

average = total / 100.0

unsubscribe_packet_data(id)

Using Variables in Mnemonics

Because command and telemetry mnemonics are just strings in COSMOS scripts, you can make use of variables in some contexts to make reusable code. For example, a function can take a target name as an input to support multiple instances of a target. You could also pass in the value for a set of numbered telemetry points.

def example(target_name, temp_number)

cmd("#{target_name} COLLECT with TYPE NORMAL")

wait_check("#{target_name} TEMP#{temp_number} > 50.0")

end

This can also be useful when looping through a numbered set of telemetry points but be considerate of the downsides of looping as discussed in the Looping vs Unrolled Loops section.

Using Custom wait_check_expression

The COSMOS wait_check_expression (and check_expression) allow you to perform more complicated checks and still stop the script with a CHECK error message if something goes wrong. For example, you can check variables against each other or check a telemetry point against a range. The exact string of text passed to wait_check_expression is repeatedly evaled in Ruby until it passes, or a timeout occurs. It is important to not use Ruby string interpolation #{} within the actual expression or the values inside of the Ruby interpolation syntax #{} will only be evaluated once when it is converted into a string. PROTIP: Using #{} inside a comment inside the expression can give more insight if the expression fails, but be careful as it will show the first evaluation of the values when the check passes which can be confusing if they go from failing to passing after waiting a few seconds.

one = 1

two = 2

wait_check_expression("one == two", 1)

# ERROR: CHECK: one == two is FALSE after waiting 1.017035 seconds

# With PROTIP to see the values at the first evaluation of the expression

wait_check_expression("one == two # #{one} == #{two}", 1)

# ERROR: CHECK: one == two # 1 == 2 is FALSE after waiting 1.015817 seconds

# Checking an integer range

wait_check_expression("one > 0 and one < 10 # init value one = #{one}", 1)

COSMOS Scripting Differences from Regular Ruby Scripting

Do not use single line if statements

COSMOS scripting instruments each line to catch exceptions if things go wrong. With single line if statements the exception handling doesn’t know which part of the statement failed and cannot properly continue. If an exception is raised in a single line if statement, then the entire script will stop and not be able to continue. Do not use single line if statements in COSMOS scripts. (However, they are fine to use in interfaces and other Ruby code, just not COSMOS scripts).

Don’t do this:

run_method() if tlm("INST HEALTH_STATUS TEMP1") > 10.0

Do this instead:

# It is best not to execute any code that could fail in an if statement, ie

# tlm() could fail if the CmdTlmServer was not running or a mnemonic

# was misspelled

temp1 = tlm("INST HEALTH_STATUS TEMP1")

if temp1 > 10.0

run_method()

end

Methods should use explicit return statements

In COSMOS 4.2 and earlier, COSMOS script instrumentation alters the implicit return value of each line. Therefore, when returning from instrumented methods, an explicit “return” keyword should always be used (Normal Ruby will return the result of the last line of a method). Note: This issue has been resolved in COSMOS 4.3, but all earlier versions must use explicit returns.

Don’t do this:

def add_one(x)

x + 1

end

Do this instead:

def add_one(x)

return x + 1

end

When Things Go Wrong

Common Reasons Checks Fail

There are three common reasons that checks fail in COSMOS scripts:

-

The delay given was too short

The wait_check() function takes a timeout that indicates how long to wait for the referenced telemetry point to pass the check. The timeout needs to be large enough for the system under test to finish its action and for updated telemetry to be received. Note that the script will continue as soon as the check completes successfully. Thus, the only penalty for a longer timeout is the additional wait time in a failure condition.

-

The range or value checked against was incorrect or too stringent

Often the actual telemetry value is ok, but the expected value checked against was too tight. Loosen the ranges on checks when it makes sense. Ensure your script is using the wait_check_tolerance() routine when checking floating point numbers and verify you’re using an appropriate tolerance value.

-

The check really failed

Of course, sometimes there are real failures. See the next section for how to handle them and recover.

How to Recover from Anomalies

Once something has failed, and your script has stopped with a pink highlighted line, how can you recover? Fortunately, COSMOS provides several mechanisms that can be used to recover after something in your script fails.

-

Retry

After a failure, the ScriptRunner/TestRunner “Pause” button changes to “Retry”. Clicking on the Retry button will re-execute the line the failed. For failures due to timing issues, this will often resolve the issue and allow the script to continue. Make note of the failure and be sure to update your script prior to the next run.

-

Execute Selected Lines While Paused

Sometimes re-executing a command or a few other lines of a script can correct problems. This can happen when commanding is over an unreliable transport layer such as UDP or a noisy serial line. For these scenarios, users can highlight the lines of the script they want to run again, right-click, and select “Execute Selected Lines While Paused”. This will run the selected lines again with the full script context (all required variables will still be in scope), and then return. Afterwards you can retry the line that failed or just proceed with “Go”.

-

Use the Debug Prompt

By selecting Script -> Toggle Debug, you can perform arbitrary actions that may be needed to correct the situation without stopping the running script. You can also inspect variables to help determine why something failed.

-

Log Message to Script Log

Not necessarily a correction for a failure, but you can log notes or QA approval that occurred after a failure using Script -> Log Message to Script Log.

If you do need to stop your script and restart, COSMOS also provides several methods to prevent restarting the script from the beginning.

-

Execute From Cursor

By clicking into a script, and right clicking to select “Execute From Cursor”, users can restart a script at an arbitrary point. This works well if no required variable definitions exist earlier in the script. A workaround can be to start using “Execute from Cursor”, immediately pause (by hitting pause or by previously setting a breakpoint), and then “Run Selected Lines While Paused” to bring in the necessary variable declarations.

-

Execute Selected Lines

If only a small section of a script needs to be run, then “Execute Selected Lines” can be used to execute only a small portion of the script.

Advanced Topics

Advanced Script Configuration with CSV or Excel

Using a spreadsheet to store the values for use by a script can be a great option if you have a CM-controlled script but need to be able to tweak some values for a test or if you need to use different values for different serial numbers.

The Ruby CSV class be used to easily read data from CSV files (recommended for cross platform projects).

require 'csv'

values = CSV.read('test.csv')

puts values[0][0]

If you are only using Windows, COSMOS also contains a library for reading Excel files.

require 'cosmos/win32/excel'

ss = ExcelSpreadsheet.new('C:/git/COSMOS/demo/test.xlsx')

puts ss[0][0][0]

Script specific screens

Starting with COSMOS 4.3, script writers can include temporary screens in their COSMOS scripts that show just the specific values relative to the script. They can even display local variables as shown below. This can be a fantastic way to display just the telemetry that is specifically relevant to what you are operating or testing. Screen definitions take the same format as normal COSMOS screens with the addition of using target name LOCAL and packet name LOCAL to gain access to script local variables. See the local_screen documentation in the Scripting Guide.

When to use Modules

Modules in Ruby have two purposes: namespacing and mixins. Namespacing allows having classes and methods with the same name, but with different meanings. For example, if they are namespaced, COSMOS can have a Packet class and another Ruby library can have a Packet class. This isn’t typically useful for COSMOS scripting though.

Mixins allow adding common methods to classes without using inheritance. Mixins can be useful in TestRunner to add common functionality to some Test classes but not others, or to break up Test classes into multiple files.

module MyModule

def module_method

end

end

class MyTest < Cosmos::Test

include MyModule

def test_1

module_method()

end

end

Further Reading

Please see the Scripting Guide for the full list of available scripting methods provided by COSMOS.